Hope, Norms, and Access: Drivers of HPV Vaccine Adoption in Nigeria

Formative research studies to develop a behavioral insights-based social media campaign to promote HPV vaccination in Nigeria have led to a series of important insights. The outcome variable used in a February 2025 study of 936 caregivers of adolescent girls aged 9-17 was “caregivers’ expectations that their adolescent girl would receive the HPV vaccine in the next 12 months”. This post helps examine how caregivers’ expectations of their child getting the HPV vaccine were shaped by individual, normative and structural factors.

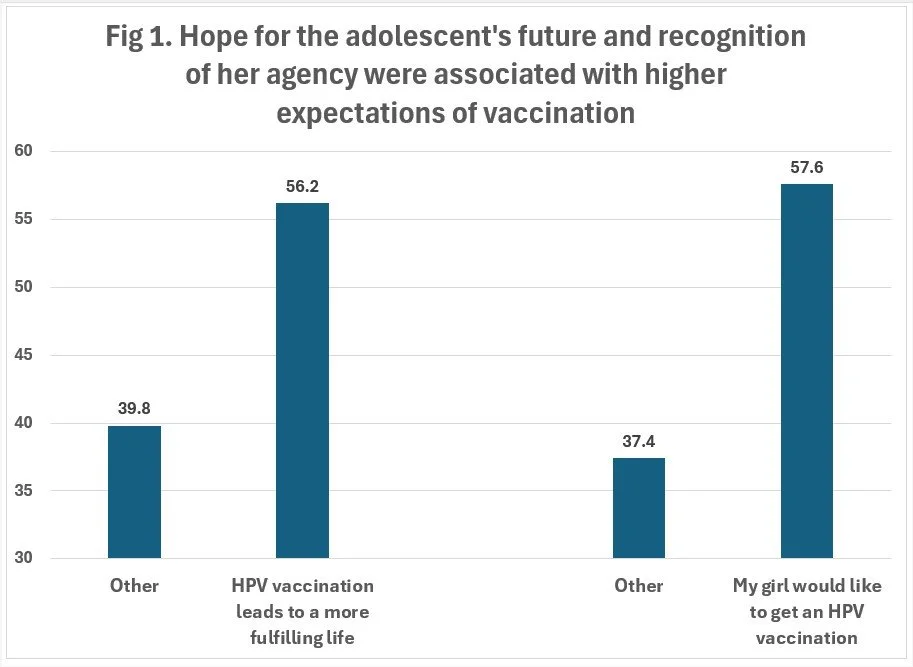

#1. Hope for the child’s future and adolescent agency increase caregiver expectations of vaccination

Figure 1 shows that caregivers who believed that HPV vaccination would help their adolescent lead a more fulfilling life were significantly more likely to expect that the child would get a vaccination—56% versus 40%. Just as importantly, the adolescent’s own agency mattered to caregivers: when caregivers believed that the child wanted to get vaccinated, expectations of vaccination rose by 21 percentage points (58% versus 37%). These findings highlight that caregivers’ hopes for their adolescent’s future and their recognition of her agency shapes their own expectations of whether their child will get vaccinated.

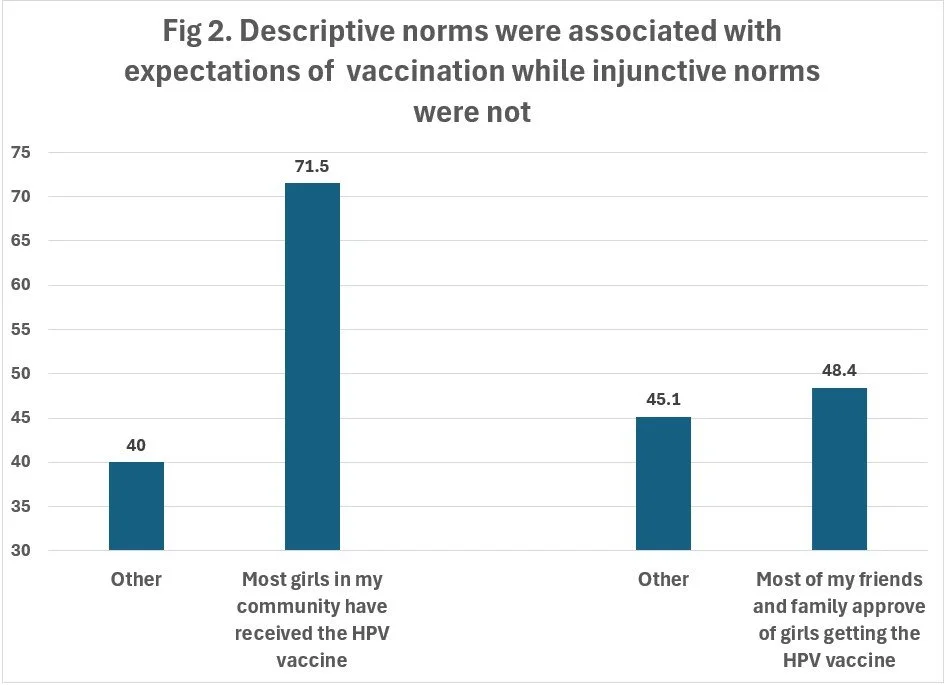

#2. Social norms strongly shape caregivers’ expectations of HPV vaccination

Figure 2 shows that social norms were the most powerful predictor of caregivers’ expectations regarding their adolescent’s vaccination. When caregivers believed that most girls in their community had received the HPV vaccine (a descriptive norm reflecting caregivers’ perceptions of what others are doing), they were 32 percentage points more likely to expect that their child would be vaccinated. Interestingly, perceived community approval of HPV vaccination (an injunctive norm reflecting caregivers’ perceptions of what others think should be done) - which we found to be influential in earlier data collected in 2024 - no longer predicted caregiver expectations of the child getting vaccinated. This shift underscores the importance of what caregivers think others are doing, rather than what they think others expect them to do, in shaping behavior.

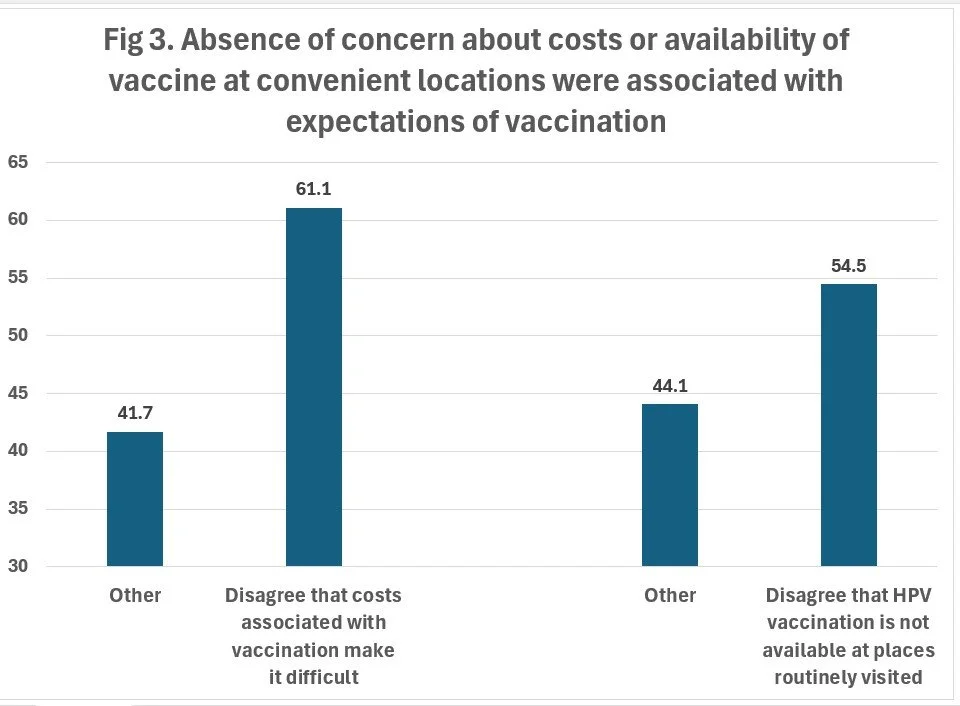

#3. Perceived affordability and convenience shape caregivers’ expectations

Structural factors play a key role in shaping vaccination expectations, as shown in Figure 3. Caregivers who were not concerned about the costs associated with HPV vaccination were far more likely to expect that their child would get vaccinated—61% versus 42%. Similarly, those who felt that the HPV vaccine was available at places they routinely visited reported higher expectations of the child getting vaccinated (55% vs. 44%). These findings highlight how reducing financial and logistical barriers can meaningfully shift caregiver expectations regarding their child’s vaccination.

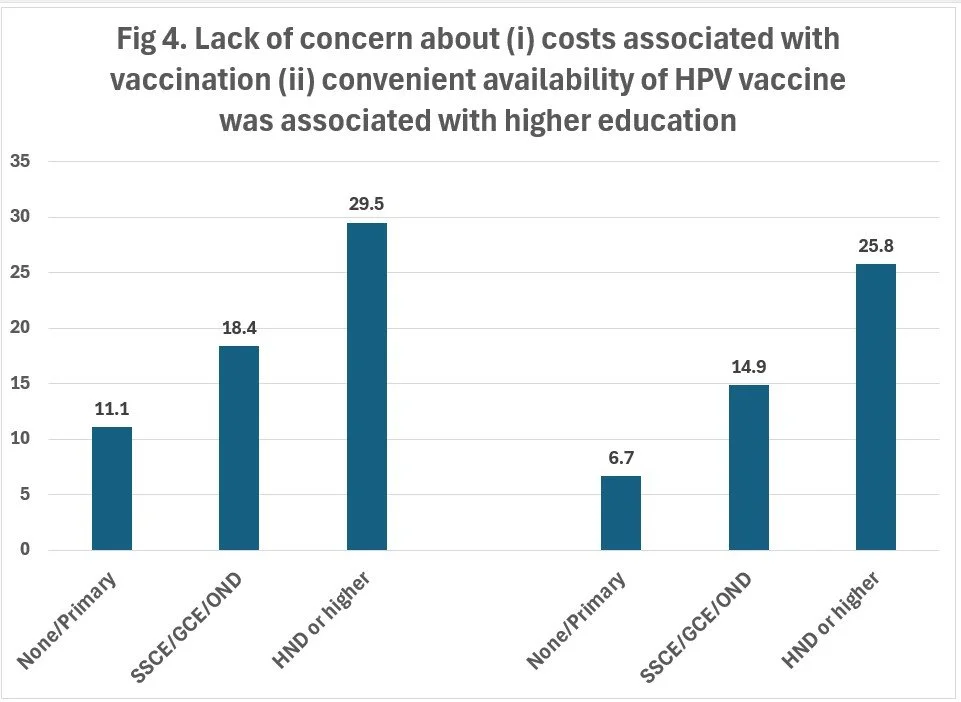

#4. Underlying inequities shape caregivers’ perceptions of access and cost

Figure 4 shows that educated caregivers were less concerned about the costs or convenient availability of the HPV vaccine. These findings may reflect deeper socio-economic differences: caregivers with greater education or financial resources may experience fewer barriers in practice—or perceive them differently. Addressing vaccine access and affordability is crucial, as is understanding the broader inequities that shape these perceptions.

Conclusion

Together, these findings offer a clear takeaway: increasing HPV vaccine uptake in Nigeria requires more than just spreading awareness. Caregivers’ expectations are shaped by hopes for their adolescent girl’s future, social norms, and structural barriers. Programs must speak to caregivers’ hopes for their child, reflect the agency of adolescents, and increase the visibility of HPV vaccination in communities. At the same time, removing cost and access hurdles—and addressing the deeper inequities that shape them—will be critical. A behavioral science lens reveals not just what drives vaccination expectations, but how programs might act on them.